A MENTAL PLAN

Death in the Mind – Richard Lockridge and George H Estabrooks

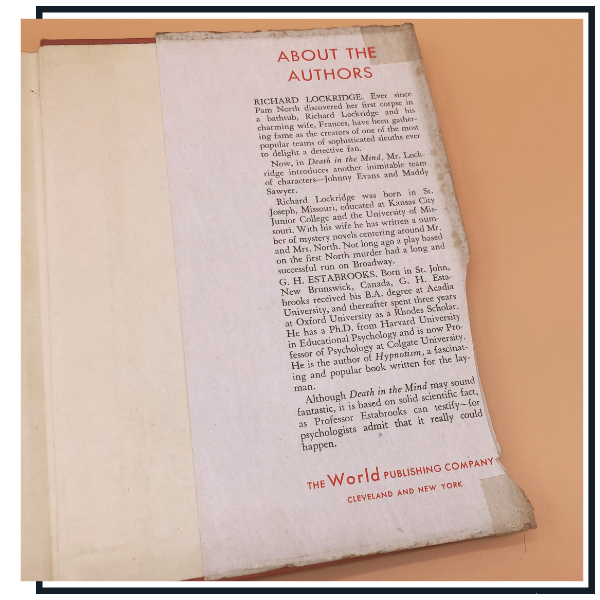

Hypnosis researcher and CIA botherer George H Estabrooks (1895-1973) is a legend of hypnotism’s recent past. But you may be surprised to learn that he co-authored a hypno-themed fiction book on precisely the wartime dangers he foresaw in hypnotism.

Published in 1945, Death in the Mind was co-written with Richard Lockridge, an American writer of detective and mystery fiction. I learned that they’d penned a book together via John Marks’ exposé on the dastardly mind-control doings of America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) – The Search for the ‘Manchurian Candidate’.

Marks explains that Estabrooks was a prescient and vocal voice on the wartime potential of hypnotism, having commenced research on the topic in the 1930s, and going on to capture many of his musings in his seminal work, Hypnotism. But, despite delivering a dossier of his ideas to CIA predecessor the Office of Strategic Services following the Pearl Harbour attack, he was (apparently) ignored.

Instead, ‘Esty’ – as Marks states was his nickname – set out to warn the world of the mindfuckery that awaited via this work of fiction.

Set during America’s intervention in World War II, Death in the Mind tells the story of Johnny Evans, a British-American secret agent working with the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to foil Nazi infiltrators on American and British soils.

Somewhat at Johnny’s side is his squeeze, Maddy Sawyer, a beautiful British agent whose job seems solely to be to relay messages between Johnny and ‘Dickie’, Britain’s top intelligence brass. One day, Maddy receives a mysterious record in the mail, which she later plays for Johnny and is found to be spoken instructions to relax and accept suggestions to sway – something Johnny dismisses as a joke. (But, if you know your Esty, is far more sinister...)

If you fancy reading the book for yourself, then please stop here for now. TBH, I found the book lacked pace and clarity at the start, so I won’t be spoiling the plot per se as the whos, hows, whys, and wherefores of all the hypnosis shenanigans and double crossings all got a bit confusing. But, in sum, Maddy is ‘turned’ into an unwitting hypno-informant, and Johnny and his buddies must enlist the help of hypnosis experts to save her and defeat the Jerrys.

There’s no one hypnotist hero or villain in the book, which is unusual for hypno-themed fiction in my experience. Instead, Johnny and his FBI colleagues consult with, variously, a psychology professor, a doctor with a knowledge of hypnotism, and a former vaudeville hypnotist with a reputation as a quack. They’re drafted into the action at various points, and pack more of a characterful punch than most other characters. But, thanks to the power of post-hypnotic suggestion, it’s mostly the operators on either side who control the subjects.

Esty’s presence is felt when our heroes learn what hypnotism can and can’t achieve, complete with references. For instance, Milton Erickson, Robert White, and John Milne Bramwell are listed as subject experts. (“Wells”* and “Brown of Oxford” are also listed, but Kev and I can’t think who they might be – answers on a postcard, assuming they’re not just fictional additions.) Experiments are also cited, as is a contemporary anecdote of a coastguard who thought a man coming to shore in a small boat was trying to hypnotise him.

The plot is quite passive, as is our hero, Johnny. Much of the time, he and his FBI buds know shit’s about to go down, but they just sort of blunder on into it. They’re particularly lax when it comes to poor Maddy. If the love of your life was colluding with the enemy, knowingly or, even more motivationally, unknowingly, wouldn’t you, oh, yer know?, keep an eye on them? Put a tail and, later, guard on them? But, no. Johnny & Co just caper about, with luck playing a bigger role in saving Maddy and defeating the Nazis than hypnotism does.

What ultimately shines through is why the CIA dismissed Esty’s ideas and scaremongering. Nothing is done with hypnosis – namely, persuading people that their friends are foes who must be informed on, or driving people nuts – that cannot be achieved without it. I was also amused when the Nazis list an array of reasons ‘turning’ a subject can fail, blaming operator error for Maddy rousing from her trance to help Johnny, such is the strength of her emotional and sexual connection to him.

Esty, however, is undiscouraged, ending the novel with his vision for winning the hypno-war. Having realised the scale and gravity of the threat of Nazis using hypnosis against the allies, our protagonists are rolling out an anti-hypnosis training programme across America, the UK, Europe, and Russia. The grand plan is to thwart the Germans with double-double-hypno-agents gleaned from the best hypnotic subjects and planted in hospitals, schools or anywhere suggestions to “relax” might be deployed.

I gather the approximate population of Planet Earth was 2.3 billion in 1940, and, as the book repeatedly (but wrongly) states, one in five people are susceptible to hypnosis. So: Esty and his fictional counterparts certainly had their work cut out!

[*Update 09.01.2024: Many thanks to ‘TistDaniel’, one of the mods at the /r/hypnosis subreddit who identified that “Wells” is Wesley Raymond Wells who wrote ‘Experiments in the Hypnotic Production of Crime’. I realise now I have written about Wells before in this post, but the Squarespace search functionality is beyond hopeless, and so I have to rely mostly on my memory! Anyhoo, I’ll plough through that paper someday soon, as ‘TistDaniel’ suggested, to search for clues on who “Brown of Oxford” is…]